Water for vegetation to capture carbon

There is scope for a modified version of the ‘Bradfield Plan’ which is a plan that outlines how to redistribute water across Australia to plant vegetation and capture carbon to stabilise the atmosphere and reduce global warming.

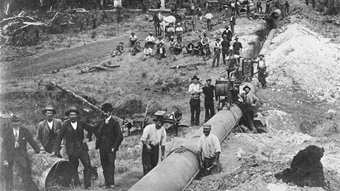

The Kalgoorlie pipeline was completed in 1903 and still operates today. It transferred water to an outback town in the desert. It is 530 kilometres (330 miles) long. It supplies water to over 100,000 people as well as farms and enterprises. If they could do it over 100 years ago, we can do it today.

Similar water transfer projects have been done in the past.

With its massive dry inland area, Australia could become the lungs of the world.

Northern Australia periodically drowns in water and constantly suffers from floods. The aim is to transfer this abundant amount of water in the north to dry inland regions in the interior.

In Queensland there has already been some work begun at a place called Hell’s Gate on the upper Burdekin River. This would be a pivotal dam site for the project.

In involves building a system of catchments, pumps, pipelines and dams. This would take water from abundant sources in Australia’s north to the dry inland interior. This would enable the initiation of a mass tree planting project in an area the size of India.

In Libya they built a network of pipes that supplies fresh water 2,820 kilometres (1,750 mi) long. It supplies 6,500,000 m3 of fresh water per day. If they can do it in a relatively poor country such as Libya we can do it in Australia.

In the North Western Australian Kimberley region there is significant potential. The Ord River project could be expanded to provide for a substantial increase in water available for tree planting projects in the interior.

Water infrastructure development and resource management must be boosted to increase the water supply from the north to allow for irrigation expansion into the Northern Territory and outback regions. There are several options including increasing storage at Lake Argyle and investigating groundwater options.

The Northern Water Infrastructure Development Fund financed a $2.2 million feasibility study by SMEC, the Snowy Mountains Engineering Corporation, which was completed last year. It concluded that the Hell’s Gate dam was feasible, in both engineering and economic terms.

However it said that as much as a decade of work was needed for engineering studies, soil surveys, environmental impact study and heritage considerations before the project would see the light of day. This is too long.

The report’s calculations were based on a dam 600 metres wide and 50 metres high impounding the 2,000 megalitres of water needed to feed a downstream hydro-electric power station and irrigate 50,000 hectares of crop land.

The stream studies pointed out that while the mean annual flow in the Burdekin was 1160 gigalitres, it could vary from 6400 gigalitres in flood years to as little as 63.3 gigalitres in dry years. And with the seasonal flow restricted to the period January to March, the mean average evaporation of nearly two metres actually exceeded the annual rainfall.

We are putting forward a revised plan. It builds on the work already under way, but requires a bigger, 120-metre high dam at Hell’s Gate to impound the water needed for its inland ambitions.

It would augment the supply by tapping waters from the Tully, South Johnstone and Herbert rivers. Downstream from the dam and its irrigation works, the water would be tunnelled through the Great Dividing Range.

The first stage would be to develop country from Charters Towers to Richmond.

The second stage would be to take surplus water from the Thomson River to the Warrego to benefit the Murray-Darling system.

The total cost of the scheme is just over $15 billion.

The project could be financed by an innovative funding model. This involves issuing debentures backed by Commonwealth and state government guarantees to overcome the objections to using taxpayers money and finance generated by the sale of carbon offset options. This would allow coupon payments on the debentures to be met.

What is needed to push the project forward is an expert agency. For example the ‘Queensland Northern Rivers Authority’ which would be similar to the Snowy Mountains Authority. It’s objectives would be to prove the concept, determine its parameters and then build and manage it to full operation. Legislation would be needed, but the Authority would be self-funding. The government would be the facilitator not the funder.

The proposal would enable the mass planting of vegetation over a vast area to capture carbon and mitigate the greenhouse effect.

It would relieve drought and the bushfire problem in Australia. It would provide clean hydro-electric electricity supply and breathe new life into many outback towns down the rivers.

There have been some reservations about the project that the cost of the water will be too high. However this has not been with similar projects in countries such as Israel and Libya.

Co-ordinated action between Australian commonwealth and state governments is required to bring these plans to fruition. We need help from the world’s people to generate the political and monetary support to make these dry, barren inland areas the lungs of the world.

We cannot let another generation of politicians run from away from providing a real solution to the global warming crisis?